Summary of the book Factfulness by Hans Rosling

The author of the book, Hans Rosling, was a Swedish physician dedicated most of his life to international health. Until he devoted himself to trying to better understand and explain the world through data.

Almost after he and his wife decided to start writing Factfulness, he was diagnosed with cancer, so he devoted the rest of his life to finishing it. Before he died, he already had the draft, and it was later that his wife published the book.

The book is so good that Bill Gates has decided to give a copy to all of last year's college graduates.

What is the book about?

In it, the author makes us see the difference assumed by the developed world between rich and poor has nothing to do with reality, according to the data that the doctor has been studying for years. He encourages us not to polarize or generalize, because within any field there is great diversity (whether micro or macro).

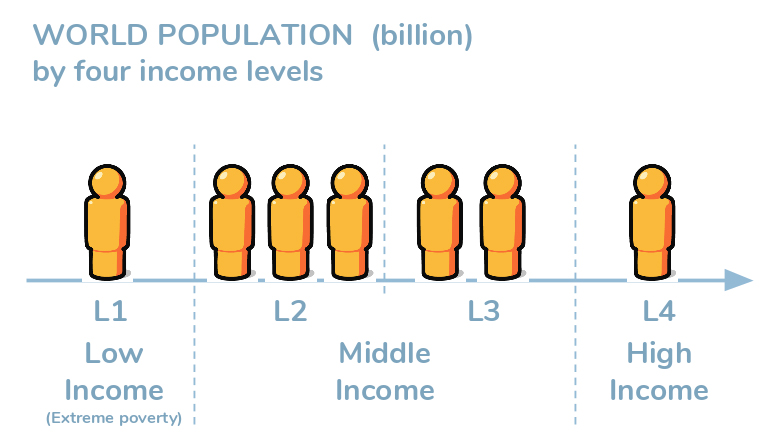

It is emphasized that if we want to analyze, from an economic point of view, the world society, we should have more classifications and stick to the income levels of families. We should not fall into the cliché of us (developed) and them (undeveloped). It would be necessary, then, to talk about four classes. The lowest would be extreme poverty. At this level, people would barely live on $1-2 a day. Above this level, and with only $4 a day, we would have 3 billion people (the graph below is proportional to the distribution of the world's population). At level three, and at $8-32 a day, people would begin to have running water in their homes and electricity stable enough to power a refrigerator. At level four would be all those people earning more than $34 a day. I understand that you, who are reading this article, are at that level.

Differences between the levels

Together with his wife, he developed an intense research work in which they showed photographs of different dependencies of houses according to the income level of the families. The curious thing about this project is that you can see that, at the same income level, the appearance of a house in Spain is practically the same as one in Nigeria, for example. It is not the culture that determines this. It is the family economy.

With all this, the book encourages us not to see things from a single ?superior? point of view. It makes the simile of observation from a skyscraper. Possibly everything below you will seem the same. But in reality there are a thousand nuances.

Hans Rosling's optimism

The subtitle of the book is ?Ten reasons why we are wrong about the world. And why things are better than you think.? This is one of the main reasons why the book has received a lot of criticism. He tries to explain, through data, that the world has improved considerably since the beginning of mankind.

A curious fact is that this gentleman dedicated himself to giving conferences to large world associations, many of them led by politicians. To his surprise, when he asked them, for example, about the percentage of girls attending school in the world, they did not even know how to answer correctly. They almost always answered below.

Like the book, we are going to explain, in a very summarized way, these ten reasons why we do not know how to interpret the world well.

The polarization instinct

The world cannot be divided in two. To think in this way is to oversimplify reality. There are many nuances. We cannot lump together those who live at level one ($1-2 a day) with those who can afford at least a fridge at home. There is a huge difference between these two groups. One has to struggle to get food for the day. While the other has to struggle to bring meat to eat something special that day.

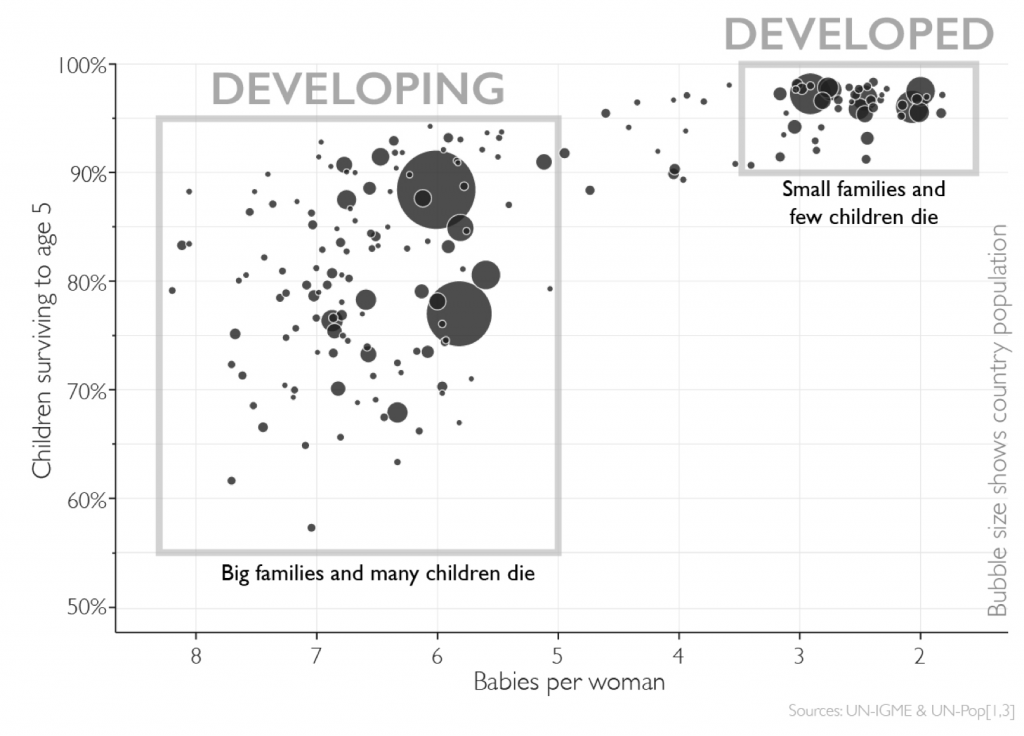

The one below is one of the graphs that caught my attention the most. It shows the birth rate per woman, according to what we know as developed and undeveloped countries. Children born per woman in 1965. In the box on the right, women in developed countries have fewer children and survive longer

Current birth rate situation. You can see how there are hardly any countries left in the left box.

Current birth rate situation. You can see how there are hardly any countries left in the left box.

The instinct of negativity

We continually receive the message that the world is getting worse. But, if we compare it to how it was a few years ago, we can see that it is not. We live longer. In better health. There is less poverty. Infant mortality has declined dramatically in the last 100 years. We have fewer deaths from war than ever before. In this article they detail some of these indicators.The instinct of the straight line

A straight line with a slope does not mean that it will continue at infinity. It may be that the world population is growing steadily, but we do not know if it will continue to do so until it reaches a tipping point.

Fear

Decisions cannot be based on fear. This is what many politicians try to instill (unfortunately) to base some decisions, or to win votes. A clear example is that of the extreme right-wing parties that try to deceive the population by saying that migrants will put nationals out of work. Possibly they have not stopped to analyze the data correctly. If they did, they would realize that migration is a catalyst for the economy, since migrants tend to fill jobs that the local population does not want to do.

Size

The numbers cannot be analyzed by themselves. Only by comparing this data can we see it in perspective. Here's a shattering fact. In 2016, 4.2 million children under the age of 1 died. This, put like this, seems (and it is) an outrage. But if we look at data from 1950, we can see that 14.4 million died.

So it is still a very high number, but obviously there has been progress thanks to advances in medicine and in the countries themselves.

Generalization

Generalization is bad. If you have taken a look at the Dollar Street project, you will see that not everyone in Cameroon lives the same way. Nor that all Chinese people have a similar cuisine. As we said at the beginning, it all depends on the level of income. If you talk about the majority, think that it can be 99% or 51%. But the majority does not mean the whole.

The destination

Societies and cultures change. We cannot assume, for example, that Africa's destiny is to be the poorest place in the world. We are living the perfect example with China. A country that was merely an agricultural country is becoming the world's largest economic power. We have also experienced it with the relocation of factories from Europe and the United States to China. As well as these we may experience it at some point. When the industrial fabric will move again in search of lower wages.

We must be attentive and aware of these changes. And have adaptability to it.

The single perspective

There is no single perspective. We cannot try to understand countries by GDP, or by the level of health. If we do it by the former, we would never deduce that the United States is a country with serious health problems. And if we only analyze by the latter, we would never admit that Cuba is one of the poorest countries in the world, despite having an excellent health system. The numbers are fine. But then you have to understand them.

Blame

We tend to look for simplistic solutions and blame external causes for our problems. We blame “the rich”, “foreigners”, “politicians”. But we rarely take our share of the blame. We criticize that China pollutes a lot, but then we continue to abuse plastic.

The urgency

We should not be in a hurry. A salesperson will always tell you that you have a few days to make the purchase, or you will run out of promotion. We cannot do the same with political decisions. The most recent case that I could comment on is that of closing nuclear power plants in Germany (and which we are replicating in Spain). The motivation is to pollute less. But it turns out that nuclear energy is a great mitigator of greenhouse gas emissions, as it takes the limelight away from polluting technologies.

Conclusions

The world is in a bad way. Yes, but it is much better than it has ever been. We must not fall into victimhood or negativity. Even so, we cannot relax either. There are still cases of racism, we continue to pollute beyond our means, and there is still extreme poverty. But it is very important to understand where we have come from, and where we are going, in order to make effective decisions.

In addition to this, we must always think about the instincts that lead us to have erroneous visions of reality and the world. Perhaps you too, after reading the book, will stop thinking of the world as developed-undeveloped, as Bill Gates has done.